Exploring healthcare providers’ perceptions of virtual reality in lung cancer treatment preparedness: a mixed-methods feasibility study for the development of EveryBreathMatters

Descriptive statistics (all 60 participants)

The study included 60 participants, 91.7% of whom were in the oncology specialty. The participants had a mean of 5 years of practice experience (SD = 4) and saw approximately 126 patients (SD = 198) annually. Most participants were unfamiliar with VR, with 26.7% somewhat unfamiliar and 26.7% not familiar at all (Table 1) summarizes the descriptive statistics.

Perceived benefits and challenges of VR use in lung cancer care

Based on our findings, healthcare providers identified numerous potential benefits and challenges associated with the use of VR in lung cancer care, as outlined in (Table 2).

Potential benefits of VR use in lung cancer care

Improved patient understanding

The majority of healthcare providers (HCP) (70%) believed that VR can enhance patient understanding. Providers in the in-depth interviews provided more context into that and emphasized that VR can help patients better comprehend their treatment journey, medical information, and care expectations through visual and interactive elements.

“I think the VR may facilitate with visual, you know, visualizations… it may definitely like increase and improve the level of understanding.” — HCP 3

Enhanced patient engagement

Sixty-eight percent of the survey respondents stated that VR can potentially enhance patient engagement in their care.

Through in-depth interviews, VR was perceived to increase engagement by making learning interactive, accessible, and aligned with how patients use technology in their daily lives.

“You are deciding the treatments among many options, or you’re under treatment… it may be a way to refresh and also to get communication from another way to serve the communication.” — HCP 3

In addition, VR could allow doctors to involve patients in information seeking, all while controlling the accuracy of the information provided, as one of the doctors said:

“Providing this technology would be at least better than patients going on Google or asking GPT, you know… whatever is being delivered is kind of controlled and quality is checked.” — HCP 2

Better management of expectations

Fifty-six percent of providers thought that VR could help better manage patient expectations. Through the interviews, healthcare providers also thought that VR can help reduce uncertainty and manage expectations more effectively, thereby decreasing the burden of clinical encounters. One of the interview participants said, “Patients usually come with a long list of questions… if you explain everything to patients, the list of questions will usually be half as long.” — HCP 7. Another provider also stated that “it would be like a great support because they can refresh… I don’t need to call them again, you know, re-explain everything.”— HCP 3.

Increased emotional support

Although the surveys showed that 72% of the respondents thought that VR would not help increase emotional support, some interview participants noted that it could help address a range of emotional needs, including alleviating anxiety, reducing distress, and offering psychological comfort to patients navigating complex care:

“I think like in this kind of extremes… it can definitely help also to visualize what’s happening to them, to reduce a little bit like their fear.” — HCP 5

“In terms of helping with their kind of stress and relaxation and things like that, that may be helpful.” — HCP 9

Potential challenges of VR use in lung cancer care

Various technology challenges were identified through the perceptions of healthcare providers (HCPs).

Patient resistance to using new technology and discomfort with technology

Seventy-two percent of providers who responded to the surveys considered it challenging to gain the trust of patients and caregivers in technology, and seventy-four percent believed that patients’ discomfort with technology would impact their acceptance of VR. One of the providers in the in-depth interviews stated that:

“More confidence in the technology, by the patients and caregivers, could be a challenge.” — HCP 2

Technology was thought to add complexity during sensitive moments.

“Adding a new complexity for a new tool that I don’t feel comfortable at all because I am 65. I live in a rural area. I don’t have even internet at home.” — HCP 3

In addition, people can be too “tired and don’t want to do the headset in the, in the chemo room or in the chemo ward.”— HCP 1. They can also face usability issues;

“You have a 70-year-old patient that’s not computer-savvy, that’s not really interested in it.” — HCP 6

People don’t even “use computers, a lot of them don’t have email addresses.” — HCP 7. Balancing technical integration with user comfort is crucial, especially for patients who are reluctant to use technology in such settings.

“If you’re approaching someone with resistance that you want to push toward this technology, it’s not a good start.” —HCP 4

Tool (VR)-related challenges

Ninety-two percent of providers believed that the challenges patients faced were unrelated to VR. However, some of the possible challenges mentioned include the difficulty in customizing the tool to meet patients’ needs.

“It’s hard to capture all of the like potential differences between patients in like one module.”— HCP 1

VR sessions can also be overwhelming for patients, considering the vast amount of information shared in a short period. The tool can also be challenging to use in the chemotherapy ward, considering the heavy weight of the headsets.

In addition, sixty-four percent thought that cost and accessibility could hinder the tool’s success.

I think the problem will be access and accessibility. I don’t know how at which costs…” — HCP 10

System-related challenges

System challenges included factors that would interfere with the safe and easy Implementation of VR-based interventions within the ongoing workflows. Eighty-eight percent of the providers also thought that the system-related challenges wouldn’t hinder the adoption of VR to support treatment education in lung cancer settings. The only issue identified was the challenging integration of this technology within the existing workflows.

“You know, it’s a headset, so it’s a little bit heavy.” — HCP 4.

Healthcare provider-related challenges

Seventy-two percent of providers believed that provider-related challenges wouldn’t impact their use of VR for patient education and support. Some possible challenges include an increased visit time due to the need to address more questions and concerns.

“I then get like another 45 minutes worth of questions that you’ve cost me 25 minutes.” — HCP 7

Additionally, some providers were concerned that using VR might “jeopardize their relationship with patients” if it were used as the primary source of information rather than a means to reinforce patients’ knowledge.

Inadequate training and support for patients

Half of the providers believed that obstacles related to patient training and support could affect the success of VR for educational purposes. One of the providers said:

“Some of them don’t even use cell phones… they don’t use the internet on them.” — HCP 7

Design preferences for the VR tool

Content preferences

Walkthroughs for orientation and comprehensive education on treatment

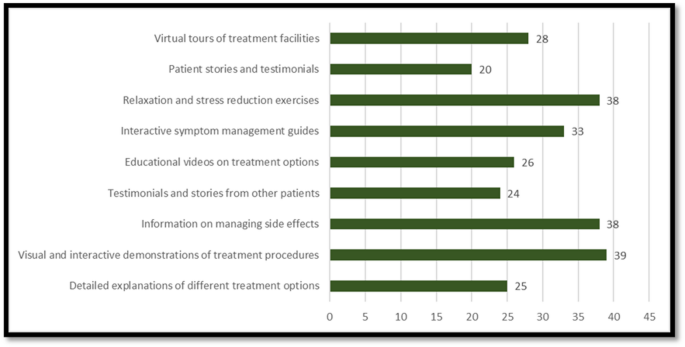

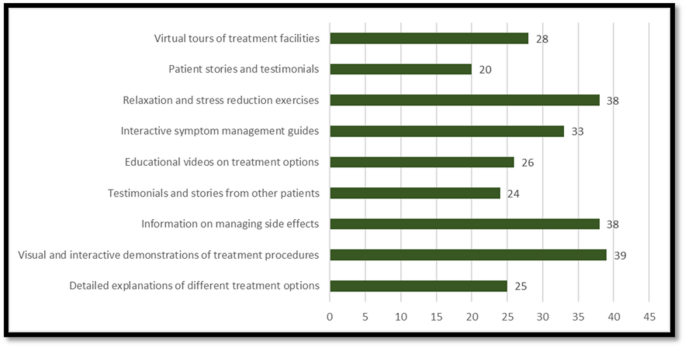

As shown in Fig. 1, 39 out of 50 providers encouraged the inclusion of simulations of treatment scenarios and visual demonstrations of treatment procedures. Providers recommended immersive and step-by-step walkthroughs to prepare patients for clinical guidelines and to help reduce anxiety. “A walkthrough to the actual infusion suite…It can definitely help to visualize what’s happening…” — HCP 1. They also noted the need for content that explains treatment options, expectations, side effects, and psychosocial implications. “Start with diagnostics… what are their advantages…” — HCP 8.

Design preferences of the providers.

Side effects and management approaches

Information on treatment, side effects, and management strategies was also encouraged (n = 38/50). Additionally, it was recommended to incorporate relaxation and stress reduction exercises (n = 38/50) and symptom management guides (n = 33/50).

“Tell me what I have to anticipate… how to reorganize my life…Explain what’s the impact on my life, not just the technical details…What to do when you are feeling shortness of breath” — HCP 3

“Provide clear instructions for when and how to contact providers… Explain when it’s time to connect with your doctor…”— HCP 5

Extra resources

Providers also recommended including educational materials related to trials, evidence, and research to help patients make informed decisions.

“Add numbers and stats… help people understand their options…” — HCP 7

“You really should help them know more about what clinical trial options are available now…” — HCP 6

Linking patients to “smoking cessation programs,” “patient portal enrollment to facilitate continuous communication,” and “patient advocacy organizations” could help them overcome the challenges of treatment, as these resources may provide more information, psycho-oncology support, and additional assistance.

Design and format preferences

Providers emphasized the importance of tailoring content to individual needs, including treatment plans, language preferences, and learning styles.

“Probably the options of subtitles in multiple languages…” — HCP 3

“I think that the good way is to be layman…” — HCP 10

Avatars and real-world mimicking

Several providers stressed the importance of designing the tool to mimic real-world roles and ensure ongoing communication, which could be achieved by introducing friendly avatars to deliver content.

“I imagine a virtual assistant who replicates the real person…” — HCP 3

Accessible information

Providers called for flexible content formats, multimodal delivery, and layered information clustered in themes to meet diverse needs and preferences. For instance, using subtitles and various audio formats, as well as short video-based learning, could be helpful. The video explanation was the most preferred format (n = 46/50). Saving information for later access could also help patients with continuous education and support.

“Save it to a personal profile so they can access it later…” — HCP 4

Timing, location, and workflow of delivery and Implementation

It was advised that the VR tools should be designed to be delivered partially in the clinic, “unlocking certain parts while they’re still in the clinic” and “giving them the option of reviewing things later at home.” Only 6 out of 50 providers believed that the interventions should be delivered at home. Twenty providers thought that it should be delivered after the visit, while 12 felt that it should be delivered before the visit, specifically when treatment plans are being established.

Providers also stated that it was essential to allow for guided self-paced options with “the first time being a more uniform guided flow” and “someone being there to help the first time they use it to troubleshoot.”

Providers believed they should be involved in delivering and using the tools (n = 26/50). They also believed that VR-based interventions should be conducted very frequently, with 17 out of 50 respondents suggesting monthly sessions and 13 out of 50 suggesting weekly sessions. For successful integration into workflows, providers recommended that providing technical support to patients (n = 44/50) and training providers to use the system to assist patients (n = 35/50) are essential.

Associations between familiarity, benefits, and challenges

As shown in Table 3, 44% of providers were neutral toward using VR to help patients understand treatment options or initiate treatment, while 40% considered it useful. Forty percent of providers were neutral towards VR assisting patients in adhering to treatment, and 36% of them felt it was useful.

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, specialty, years of practice, number of patients seen annually, and familiarity with VR were not associated with the perception of VR as useful in treatment education, initiation, and adherence support.

Usefulness of VR in understanding treatment options

As shown in (Table 4), people who thought VR could improve patient understanding (OR = 0.04 [0.001–0.39], p = 0.0019), management of expectations (OR = 0.16 [0.03–0.67], p = 0.014), and emotional support (OR = 0.13 [0.03–0.53], p = 0.005), were more likely to think it is useful in supporting patients’ understanding of treatment.

Usefulness of VR in initiating treatment

People who thought VR could improve patient understanding (OR = 0.04 [0.001–0.39], p = 0.0019), management of expectations (OR = 0.16 [0.03–0.67], p = 0.014), and emotional support (OR = 0.13 [0.03–0.52], p = 0.005), were more likely to think it is useful in supporting patients’ understanding of treatment.

Usefulness of VR in adherence to treatment

People who thought VR could provide emotional support to patients were more likely to believe it is useful in supporting patients’ adherence (OR = 0.07 [0.01–0.31], p < 0.001).

link